The Project

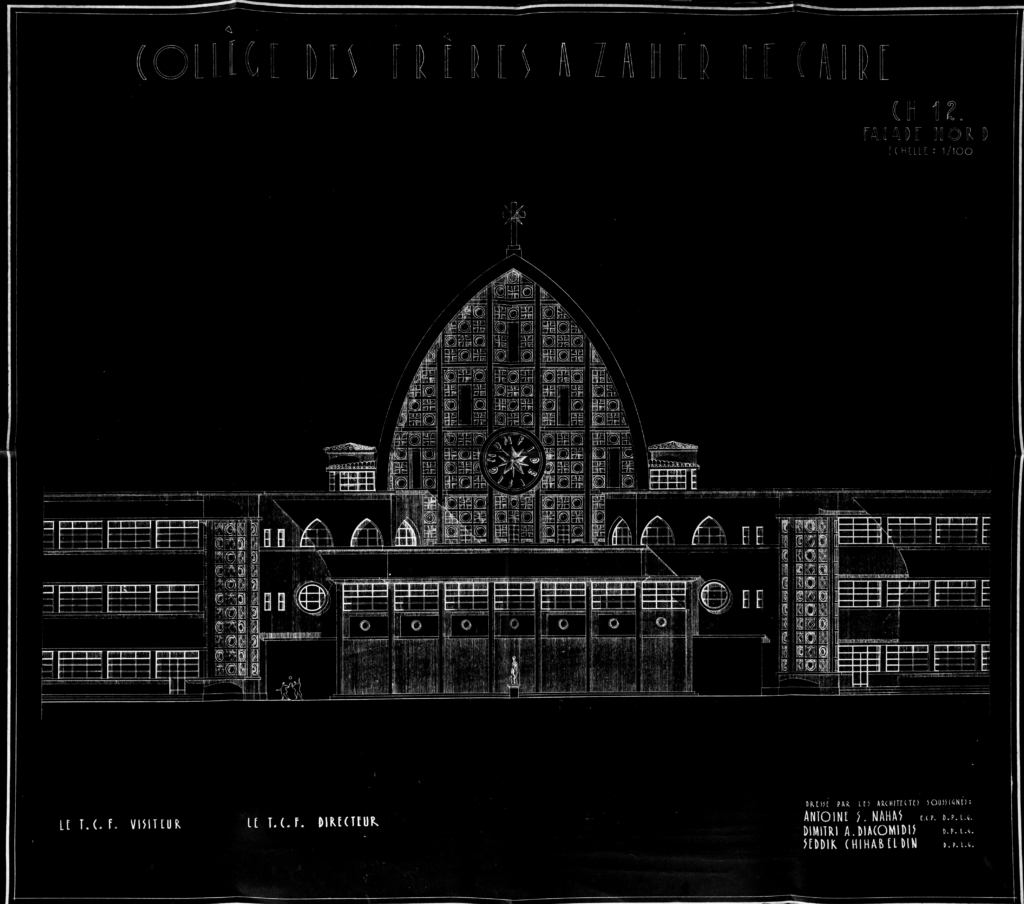

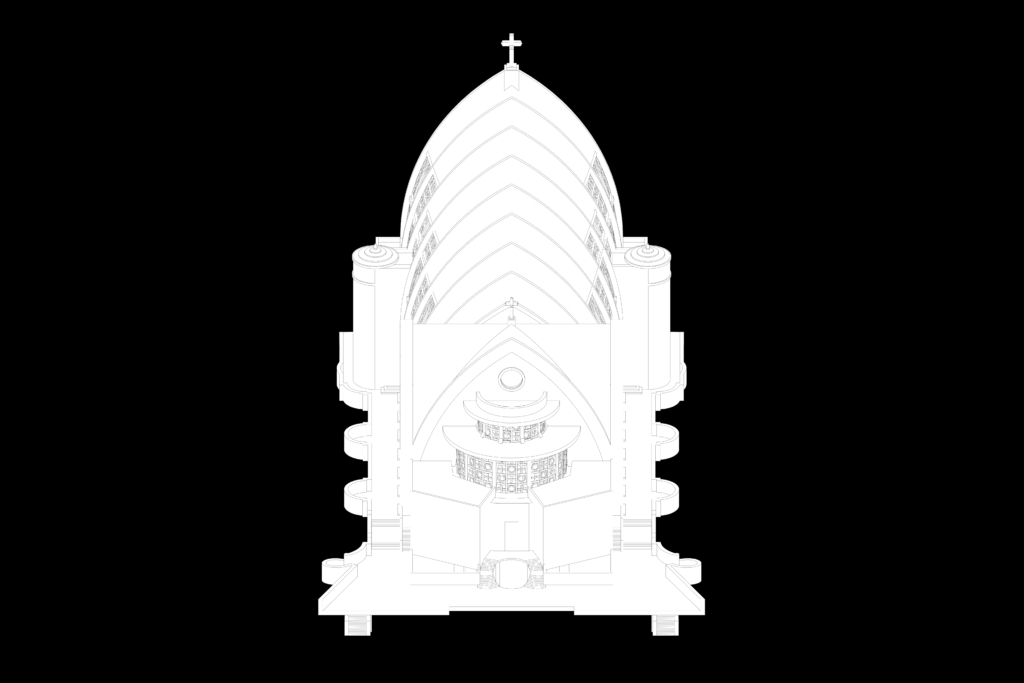

The Chapel of Collège de La Salle des Frères in Daher, Cairo, Egypt was built in the 1950s, as part of an expansion project of the original 1902 building, by three alumni of the school, Egyptian architects, Antoine Selim Nahas, Seddik Chihab El Din and Dimitri Diacomidis, the former was one of Egypt’s most prominent architects during the 20th century. It was managed by alumnus, Jean Moscatelli, one of the founders of Art and Liberté movement.

The imposing house of worship is a unique blend of modernist and classical architecture, featuring stained glass panels crafted by the master glass maker Gabriel Loire, from Chartres, France.The chapel is perfectly integrated into the school complex, it forms its heart. A landmark, it was the largest building in the neighborhood. Those who designed it did not lack audacity. It is a testament to the ambitious architectural aspirations of the 1950s, driven by the promise of reinforced concrete.

In 2020, 70 years later, a project that began as architectural photographic documentation evolved through detailed archival processing into a cross-disciplinary exploration of a transformative era in Egypt. Three alumni, with backgrounds spanning photojournalism, documentary, storytelling, and architecture, combined their expertise to create an architectural analysis informed by photography and historical research that expands the archive’s potential, resulting in a rich, multilayered narrative that interweaves the stories of remarkable individuals, their community, and their nation. Through the story of the chapel, its construction and its protagonists, the trio explores the sociopolitical, economic and demographic shifts that shaped Egypt in the 1950s. This period saw the fall of the monarchy, the rise of the Free Officers, Nasser’s nationalism and Pan-Arabism. The tripartite aggression during the Suez Crisis and the subsequent expulsion of foreigners from Egypt drastically altered Cairo’s cosmopolitan nature, leaving a lasting impact on the school. The research also examines the history of les Frères des Ecoles Chrétienne, their presence in Egypt since the 19th century, their role in shaping modern education, and their ties to French cultural influence in a country under British control. It explores their relationship with Egyptian authorities and how they adapted to the 1950s sociopolitical shifts. It also questions the motives behind building such a monumental structure within a school, was it purely functional, a symbol of influence, or a statement? Moreover, the research provides an in-depth analysis of the chapel’s design within the context of architectural movements.

The work is based on a combination of archival materials and architectural/documentary photographs taken by the authors. These materials contain rare, unpublished and unseen architectural drawings, archival photos of the construction, correspondences, meeting notes, articles and an unpublished autobiography sourced from the archives of the school in Cairo and Alexandria, the congregation in Rome and Lyon as well as Atelier de Loire in Chartres, France and the descendants of the three architects.

This project aims to transform the Chapel into a living reservoir of personal and collective memory. In response to the alarming state of Cairo’s historical architecture, threatened by neglect, insensitive interventions, and demolition, the authors have invested their personal resources to document and preserve one building at a time.

Their deep connection to this chapel informs a balanced approach between the personal and scholarly, aiming to prepare it for visitors and scholars, with a permanent museum that will be established, showcasing architectural drawings, archival materials and a 3D model. Integrated QR codes will grant access to digital archives, 3D Exploration, and multimedia content, while curated guided tours will offer a journey through the chapel’s architectural and sociopolitical layers.

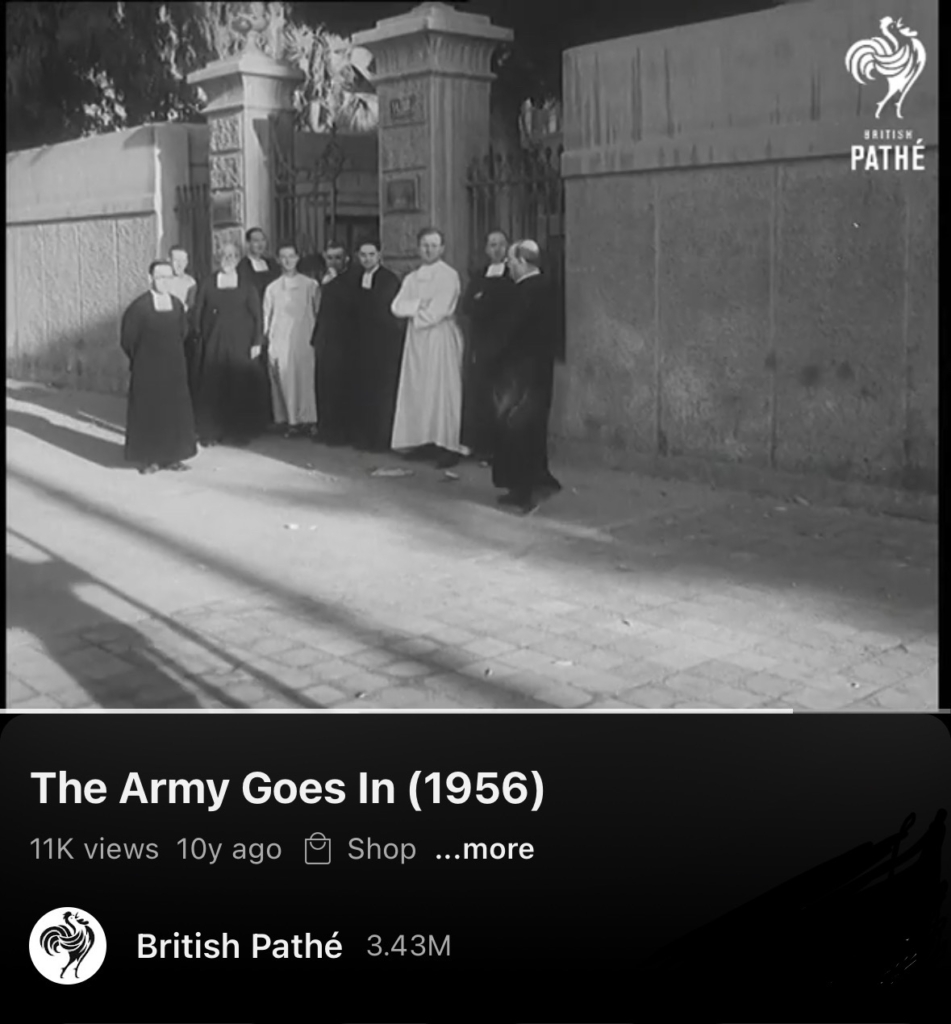

With the fall of the monarchy in 1952 and the establishment of a republic, Egypt underwent profound sociopolitical and demographic transformations, aligning itself with the broader wave of independence movements across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. The Free Officers, led by Gamal Abdel Nasser, sought to assert Egyptian sovereignty, a vision that crystallized in 1956 when Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, a strategic global waterway that had long been controlled by foreign interests.

This move was met with military intervention from Britain, France, and Israel, who sought to regain control and curb Egypt’s growing independence. At this pivotal moment, Egypt’s defiance mirrored similar struggles worldwide, from India’s non-aligned stance to Algeria’s brewing resistance against French rule.

The U.S., leveraging economic and diplomatic pressure, and the Soviet Union, issuing stern warnings and threats of military retaliation, forced the tripartite force to withdraw, allowing Nasser to secure Egypt’s control over the canal. This victory bolstered Egypt’s position as a leader in the emerging non-aligned movement, challenging colonial legacies not just locally but globally.

Britain and France, facing a shifting world order, retreated from their former influence, a retreat echoed in other colonies gaining independence during this era.

In the years following the Suez Crisis, Egypt’s policies reshaped its society. Many non-Egyptian residents, British, French, and Jewish communities among them, left, some expelled, others departing amid Nasser’s 1961 nationalization of industries. This reflected a broader trend in newly independent nations, like Ghana or Indonesia, where economic control was reclaimed at the expense of multicultural legacies.

Egypt’s identity debates, long-standing and complex, found a firm answer under the Free Officers, prioritizing national unity over diversity. Cairo, once a cosmopolitan hub, became more homogeneous, a shift paralleled in cities across the decolonizing world.

During that period, Egypt imposed limitations on imports due to various economic factors. The Free Officers assumed power following the conclusion of the Korean boom and the downturn in cotton markets. This led to cautious fiscal, monetary, and foreign exchange policies in the initial years of their rule.

Controls over foreign exchange were strengthened in 1953, including restrictions on imports. Additionally, the Egyptian economy experienced a general recession from 1952 to 1954, compounded by land reforms and sporadic seizures of private property, contributing to an atmosphere of uncertainty.

These policies reflected the government’s push for economic self-sufficiency, but they also limited trade and foreign investment.

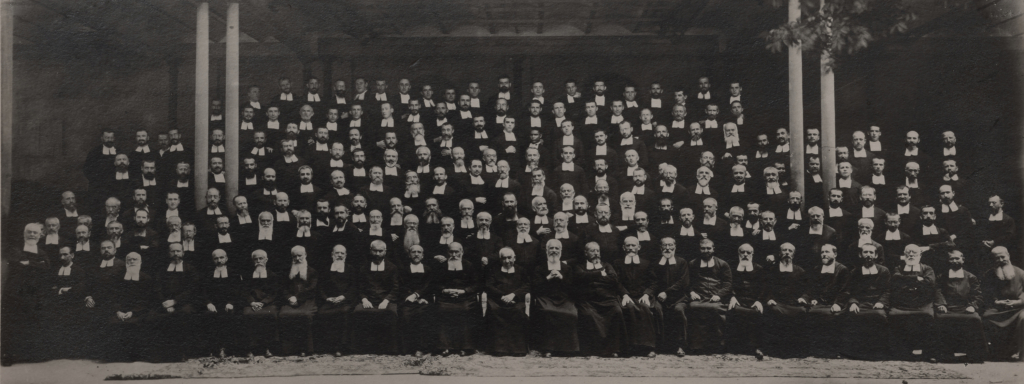

Les Frères des écoles chrétiennes are a Catholic religious institution founded in France in the 17th century by Saint John Baptist de La Salle. The Brothers are dedicated to providing accessible education to all social classes, especially the poor and disadvantaged, through free schools supported by larger fee-paying institutions. In Egypt, their history dates back to the reign of Muhammad Ali Pasha, who viewed education as a crucial factor in the country’s development.

Their expansion reached its peak in 1933 with 33 establishments, including free schools, fee-paying institutions, law and commercial schools, and vocational training centers. They played a crucial role in shaping the modern education system and fostering the development of a French-speaking educated class in a country under British control.

In the early 1950s, Les Frères des écoles chrétiennes had already been present in Egypt for more than a century.

At that time, more than 125,000 young men had graduated from their schools, with establishments in each of the three major cities in the Delta, and also in Upper Egypt, seven in Alexandria, seven in Cairo, and two in Port Said and Ismaileya.

These schools had over 9,000 students, half of whom were in the capital.

Since the end of World War II, given the rapid socio-demographic evolution of the neighborhood, there was an urgent need to relocate part of Saint Joseph ‘Khoronfish’ College, the first Brothers’ establishment in Cairo, which had become too small to accommodate a constantly growing student population.

The Brothers saw that Collège De La Salle in Daher was a suitable option for their expansion project due to its accessible location and the diversity of the neighborhood population and its strong Christian presence.

This school, offering primary and preparatory education, had an original four-story building constructed in 1902. Additionally, the unbuilt area offered sufficient space for constructions without disrupting the school year, allowing the Brothers to accommodate the increasing number of students and realize their development vision.

For several years, the Brothers had tried to obtain permission to add classes above the fourth floor of the original building. However, a neighboring catholic school, upon learning of this project and fearing that the expansion of the College would threaten their own operation, intervened with the Oriental Congregation in the Vatican, and stoped the project.

Finally the veto issued against the project was finally lifted in 1949, after years of negotiations. This endeavor, led by Fr. Aubert-Joseph, marked not just the addition of few classes but the realization of what he referred to as a ‘modern educational palace’. A project that will incorporate a chapel at its core intended to be the landmark of the neighborhood, a testament to the ambitious architectural aspirations of the 1950s, driven by the use of reinforced concrete techniques.

Visual Documentation

Architectural Photography:

The architecture of the chapel is being documented in its vacant state.

The documentation includes both the exterior and interior, showcasing the design elements and the transformative effect of the stained glass under various lighting conditions throughout the day and across different seasons.

A drone is being utilized to provide a contextual view of the chapel within the school complex, the neighborhood, and the city

Significant effort is being dedicated to meticulously photograph the intricate details of the stained glass, as well as the furniture, doors, and the organ within the chapel.

Documentary Photography:

In parallel, the project focuses on documentary photography, aiming to register the life within the chapel and how students interact with and perceive the building.Attending masses and various events, the preparations, choir rehearsals, and grand celebrations are being documented.

Additionally, portrayals are sought of the moments when students and alumni, during breaks or after school hours, seek solace within the chapel, engaging in personal prayer or meditation.

Archival Processing

Meticulous ongoing archival processing, including surveying, arranging, and categorizing materials, will be conducted in the future.

Scanning and digitization techniques will be employed as part of this process. Each document, photograph, architectural drawing, and other material will undergo careful scanning using high-quality equipment.

This process will create digital replicas of the original materials, documenting their content and visual characteristics with precision to make them more accessible, ready for study and analysis, ensuring their long-term availability.

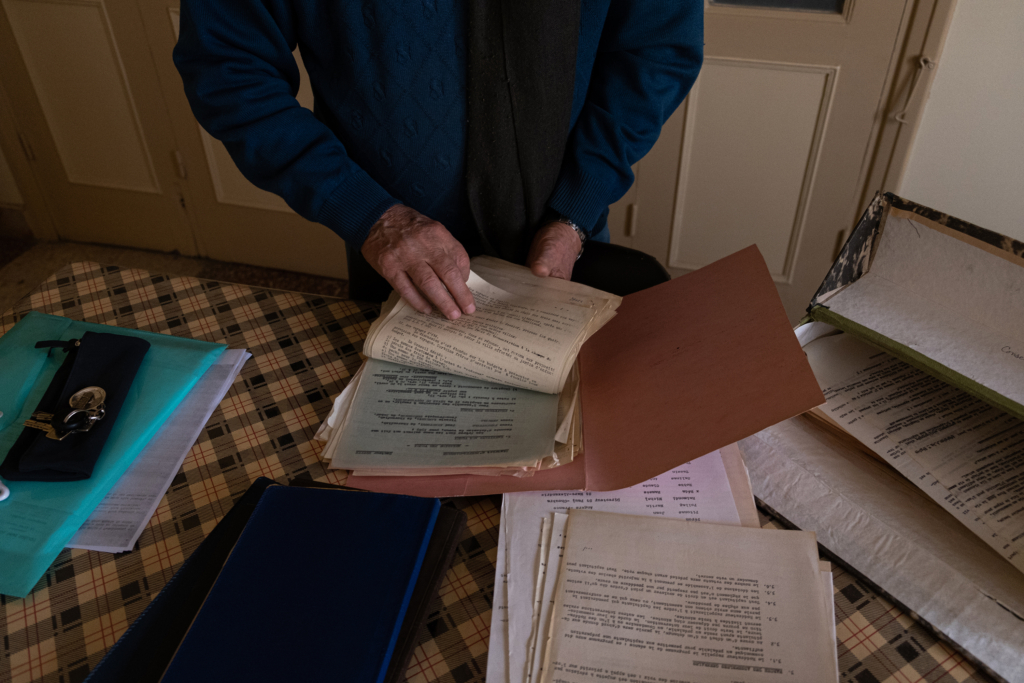

Direct work was conducted in the archives of the congregation in Egypt and Rome, Atelier Loire in Chartre, with remote collaboration through correspondences with the congregation’s archive in Lyon.

The archive of Les Frères des écoles Chrétiennes in Egypt is primarily divided among two institutions: Le Collège De La Salle Daher and St. Joseph – Khoronfish. There is also an archive at Collège St. Mark Alexandria, but it specifically relates to the Alexandrian school.

A vast collection of documents and recordings of the congregation’s activities in Egypt since the 19th century is housed in the archive, including meeting notes, class lists, letters, the brothers’ journals, annual magazines, photographs, and architectural drawings, as well as administrative paperwork such as contracts and budgeting records.

Close collaboration was established with Fr. Jean Hérault, a French brother in his late 70s, who arrived in Egypt in 1977 and has recently started his new role as archivist.

Meticulous ongoing archival processing, including surveying, arranging, and categorizing materials, will be conducted in the future.

Scanning and digitization techniques will be employed as part of this process. Each document, photograph, architectural drawing, and other material will undergo careful scanning using high-quality equipment.

This process will create digital replicas of the original materials, documenting their content and visual characteristics with precision to make them more accessible, ready for study and analysis, ensuring their long-term availability.

Direct work was conducted in the archives of the congregation in Egypt and Rome, Atelier Loire in Chartre, with remote collaboration through correspondences with the congregation’s archive in Lyon.

The archive of Les Frères des écoles Chrétiennes in Egypt is primarily divided among two institutions: Le Collège De La Salle Daher and St. Joseph – Khoronfish. There is also an archive at Collège St. Mark Alexandria, but it specifically relates to the Alexandrian school.

A vast collection of documents and recordings of the congregation’s activities in Egypt since the 19th century is housed in the archive, including meeting notes, class lists, letters, the brothers’ journals, annual magazines, photographs, and architectural drawings, as well as administrative paperwork such as contracts and budgeting records.

Close collaboration was established with Fr. Jean Hérault, a French brother in his late 70s, who arrived in Egypt in 1977 and has recently started his new role as archivist.

Preservation of the rare archive of Antoine Selim Nahas

The chapel’s original drawings which were discovered in the school’s archive belongs to one of the most prestigious Egyptian architects, Antoine Selim Nahas, who remained obscure for years due to his shy, private nature and the loss of his archives.

Architectural Analysis

An on going architectural documentation started with an in-depth study and refinement of the original plans, ensuring clarity for readers and serving as a foundation for a new series of 3D and 2D drawings and diagrams aiming for simplifying the understanding of the building for a broader audience.

The process of close examination of the original plans and careful doctoring of its weathered parts was crucial for the comprehension of the intricate details envisioned by the architects. This systematic, yet rigorous, process allowed the decoding of the spatial characteristics and qualities of the edifice, revealing the proportional system upon which the architecture was crafted.

The architectural documentation encompasses an elaborate digital 3D model intended for generating a physical model, to be showcased in a temporary and permanent exhibition.

A thorough reading across the archival photos, correspondences and architectural records, especially the manifesto written by Seddik Chihab El Dine, informed a holistic comprehension of the architecture. The overlay of these three main mediums blended into a primary viewport for the research process.

The analysis portrays the moment of a critical stance of the three architects towards the prevailing modernist ideologies at the time. Offering an architectural statement, which transcends mere functionalism, carrying and inheriting in its DNA, classical architectural principles deeply rooted in ancient Egyptian architectural heritage.

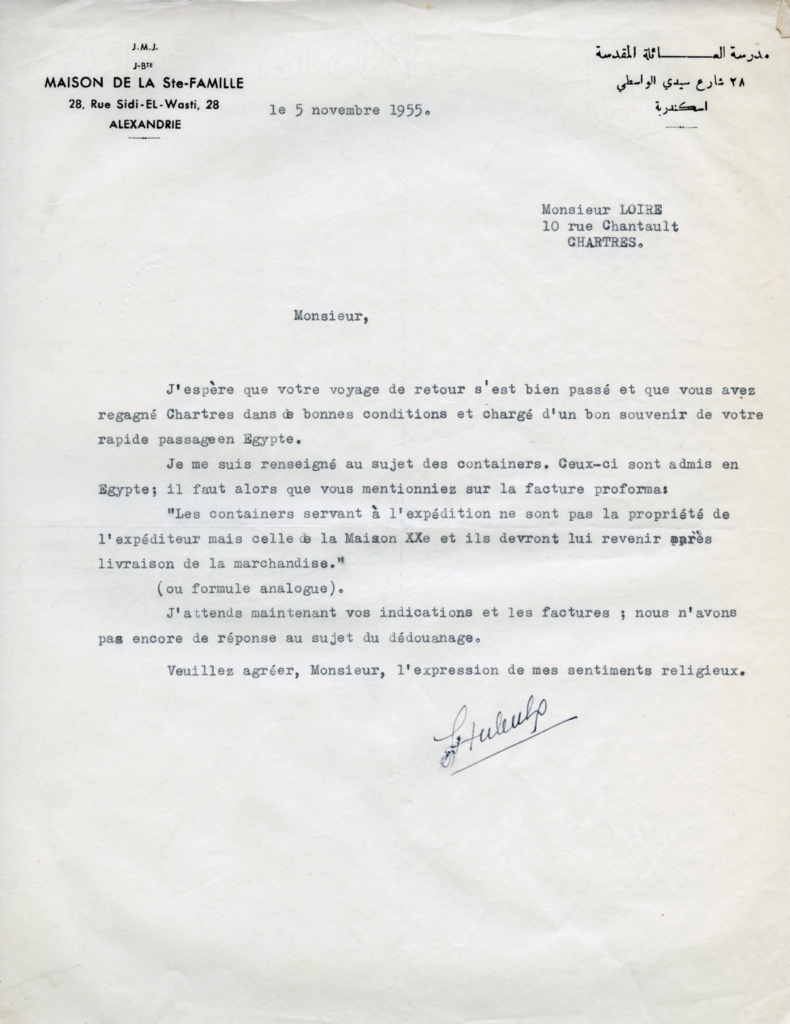

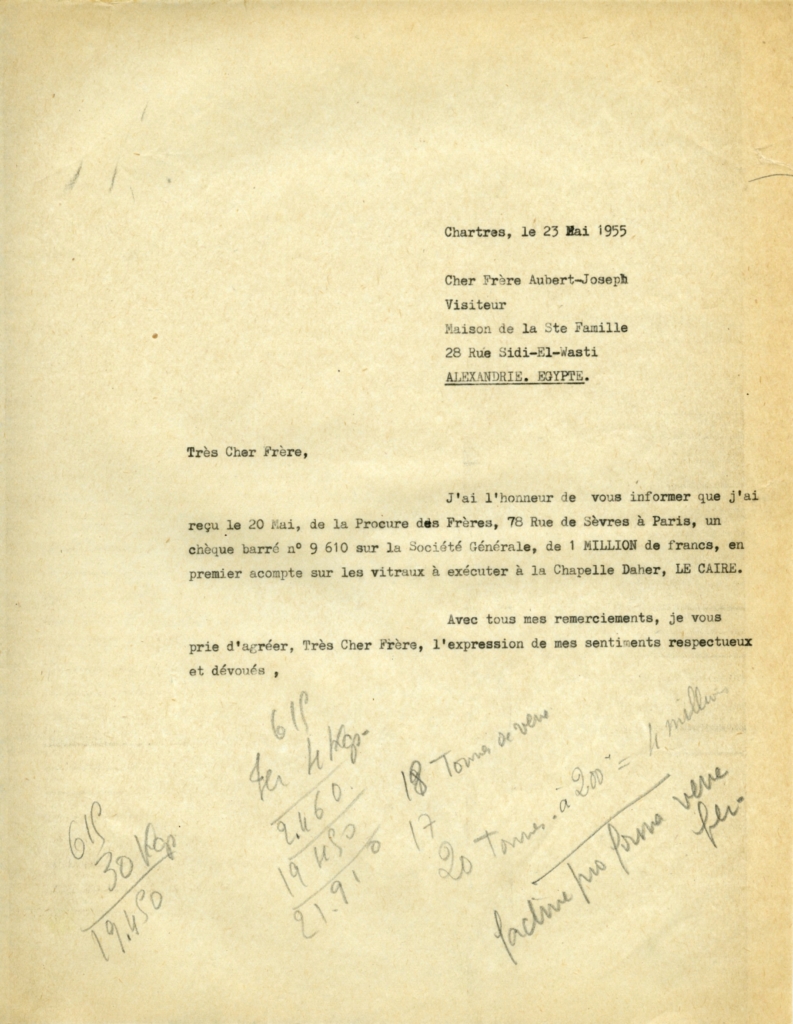

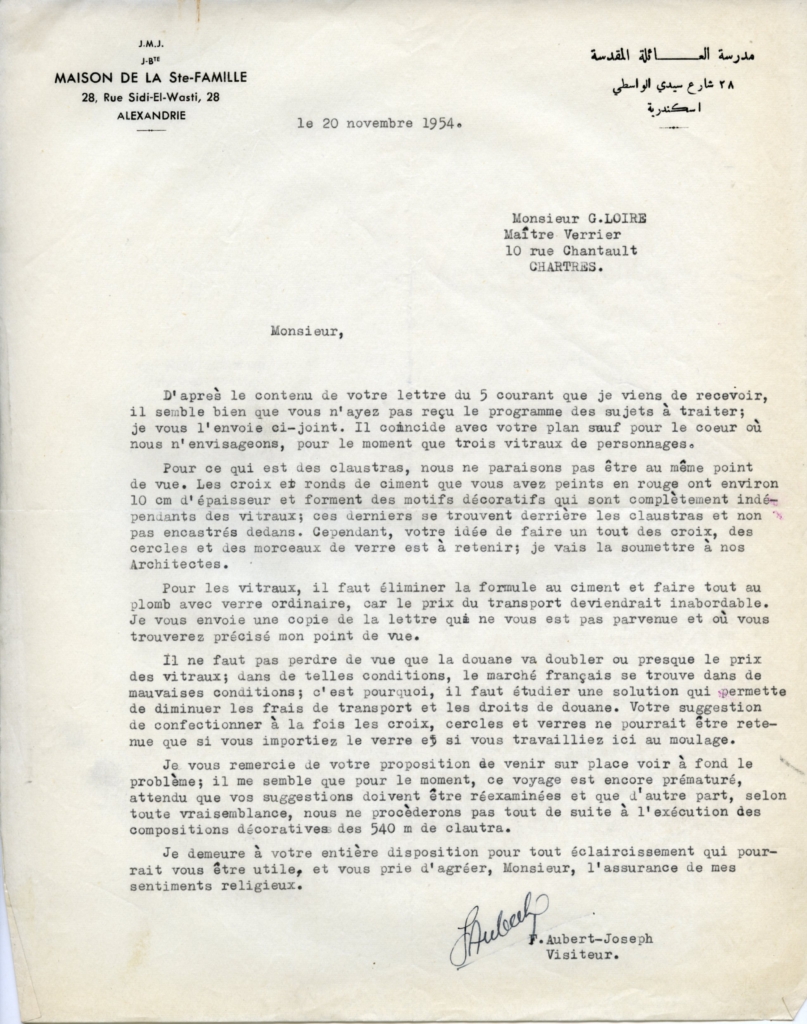

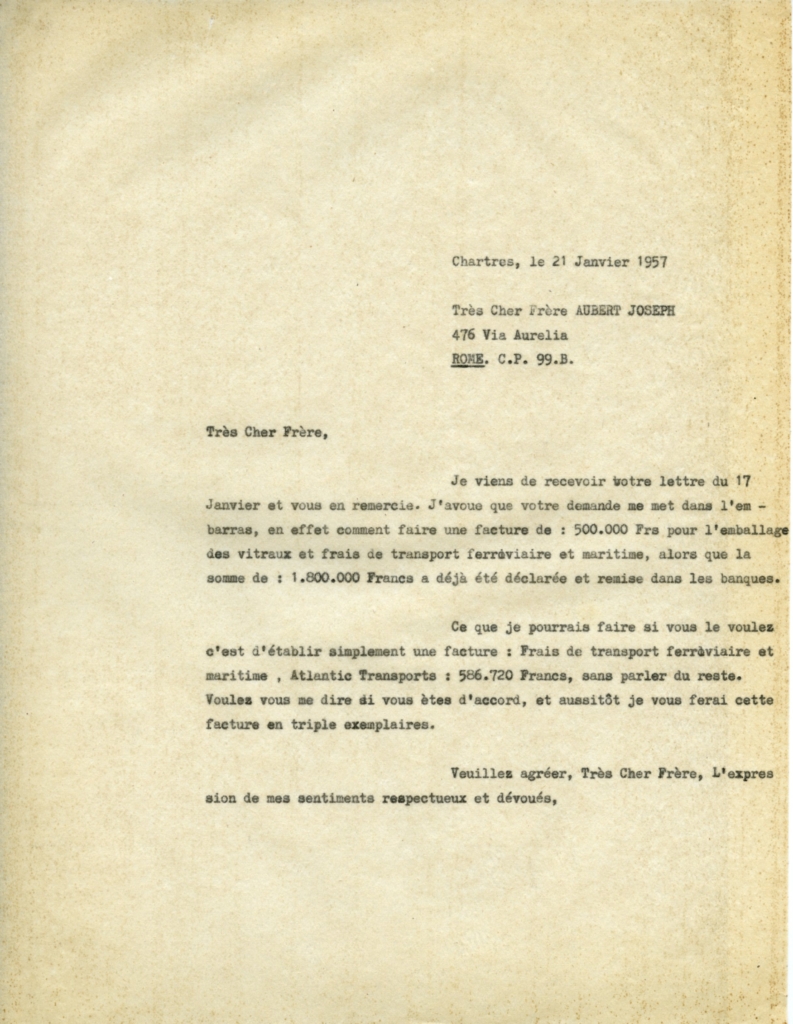

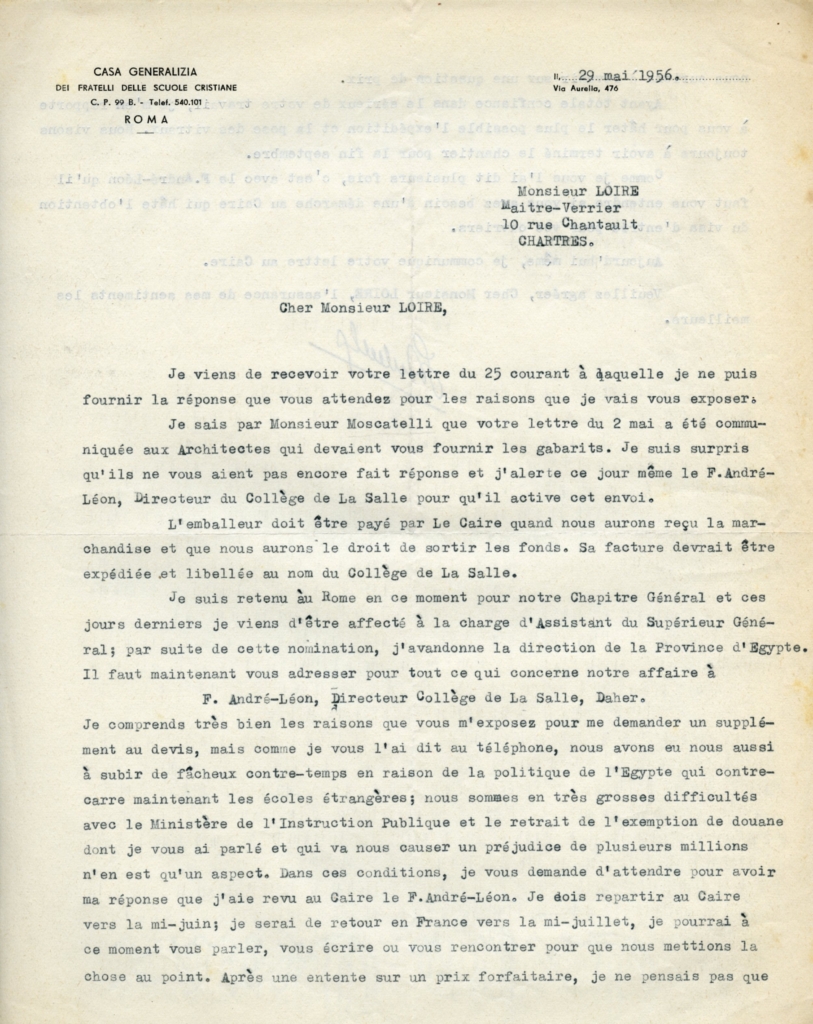

Archival Correspondences

More than 80 letters depicting the detailed exchanges between Fr Aubert and Mr. Gabriel Loire regarding the design process and financial aspects.

The correspondence reveals the economic and political constraints of the moment, which restricted imports of unnecessary products, and the need for caution in their writings due to the strict censorship by Egyptian security.

The cost of the stained glass windows was a significant factor, an original ambitious plan consisting of 23 biblical characters and symbolic scenes had to be drastically sacrificed due to the extremely high cost.

The political tensions between Egypt and France peaked after the nationalization of the Suez Canal, Fr. Aubert clearly expressed this in one of his letters, in which he said, “Due to Egypt’s policy, which is now hindering foreign schools, we are facing major difficulties with the Ministry of Public Instruction, and the withdrawal of customs exemption will cause us a loss of several million (francs)”

Despite arriving just two days after the tripartite aggression, Mr. Ronsin, the French glass installer, along side the brothers and Egyptian workers were able to successfully complete all of the work.

However, further examination of the school’s archival documents reveals that certain details remained unfinished. It was the local team, under the direction of Brother Cornélis, who undertook the completion. An expert observer may notice one or more details in the East facade that testify to this change in the team.

The Organ of Rivoli

This set of documents under the name of “l’Orgue de Rivoli” contains information about the Chapel’s organ, Originally built for the famous cinema Rivoli that was burned during the anti British riots in 1952.

The country’s largest and only theater organ was bought and installed in a wooden housing designed by architect Naom Chébib, a former student of the school, designer of Cairo Tower and Al Ahram Building.

During the 1960s, discussions about the renovation of this organ were influenced by the gradual disappearance of the neighborhood’s cosmopolitanism, resulting in a change in the student population.

This was a consequence of President Nasser’s nationalist ideology and pan-Arabism and the suez crisis, which led to the expulsion of many foreigners and the nationalization of their properties.

Faced with these changes, the brothers started a deeper cultural adaptation, raising questions about the importance and necessity of renewing such an organ, considering that Coptic liturgy would increasingly take precedence in celebrations where this instrument is not used. All of this was accompanied by emerging financial pressures.

The Stained Glass

In 2022, after corresponding with his descendants, a visit to Gabriel Loire’s workshop in Chartre was arranged. Welcomed by his grandchildren Hervé and Bruno Loire, the workshop introduced the process of making ‘Dalle de Verre’ or Slab Glass, a stained glass technique invented by Parisian glass maker Jean Gaudin during the 1930s, which was used in the chapel. The photo documentation illustrates the making process, which involves slabs of colored glass, 20 to 30 centimeters square or rectangular and up to 3 centimeters thick, shaped by breaking with a hammer or cutting with a saw. The resulting pieces may have chipped or faceted edges to enhance refraction and reflection effects.